The Indian government should prevent and prosecute mob violence by vigilante groups targeting minorities in the name of so-called cow protection, Human Rights Watch said in a report released in March. The 104-page report, “Violent Cow Protection in India: Vigilante Groups Attack Minorities,” describes the use of communal rhetoric by members of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to spur a violent vigilante campaign against consumption of beef and those engaged in the cattle trade. The victims are predominantly Muslims and Dalits.

Summary by Human Rights Watch:

Members of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), since coming to power at the national level in May 2014, have increasingly used communal rhetoric that has spurred a violent vigilante campaign against beef consumption and those deemed linked to it. Between May 2015 and December 2018, at least 44 people—36 of them Muslims—were killed across 12 Indian states. Over that same period, around 280 people were injured in over 100 different incidents across 20 states.

The attacks have been led by so-called cow protection groups, many claiming to be affiliated to militant Hindu groups that often have with ties to the BJP. Many Hindus consider cows to be sacred and these groups have mushroomed all over the country. Their victims are largely Muslim or from Dalit (formerly known as “untouchables”) and Adivasi (indigenous) communities.

This report details 11 vigilante attacks that killed 14 people and the government response. It examines the link between cow protection and the Hindu nationalist political movement, and the failure of local authorities to enforce constitutional and international human rights obligations to protect vulnerable minorities. In most of the cases documented here, families of victims, with the support of lawyers and activists, were able to make some progress toward justice, but many families fear retribution and do not pursue their complaints. The report also examines the impact of the attacks and the government response on those whose livelihoods are linked to livestock, including farmers, herders, cattle transporters, meat traders, and leather workers.

In almost all of the cases, the police initially stalled investigations, ignored procedures, or even played a complicit role in the killings and cover-up of crimes. Instead of promptly investigating and arresting suspects, the police filed complaints against victims, their families, and witnesses under laws that ban cow slaughter. In several cases, political leaders of Hindu nationalist groups, including elected BJP officials, defended the assaults. In a particularly egregious case of political opportunism, after two people including a police officer were killed in mob violence in December 2018 in Uttar Pradesh state, the chief minister described the incident as an “accident,” and then went on to warn, “Illegal slaughtering, and not just cow slaughter, is banned in the entire state.”

In July 2018, India’s Supreme Court issued a series of directives for “preventive, remedial and punitive” measures to address “lynching”—the term used in India for killing by a mob. While cow protection is an emotional issue for many Hindus, the Supreme Court denounced violent attacks by so-called cow protectors, saying: “It is imperative for them to remember that they are subservient to the law and cannot be guided by notions or emotions or sentiments or, for that matter, faith.”

Human Rights Watch calls upon national and state governments to enforce the Supreme Court directives; ensure proper investigations to identify and prosecute perpetrators regardless of their political connections; initiate a public campaign to end communal attacks on Muslims, Dalits, and other minorities; reverse policies that are impacting livestock-linked livelihoods, particularly in rural communities; and hold to account police and other institutions that fail to uphold rights because of caste or religious prejudice.

The Politics of Cow Protection

Cow slaughter is forbidden in most parts of Hindu-majority India. However, over the last few decades, Hindu nationalists have led a political campaign complaining that the authorities do not do enough to enforce the ban and stop cattle smuggling. Since beef is consumed largely by religious and ethnic minorities, BJP leaders, in seeking to appeal to Hindu voters, have made strong statements about the need to protect cows that have enabled, and at times may have incited, communal violence. Narendra Modi, when he was chief minister of Gujarat state and during the 2014 national election campaign, repeatedly called for the protection of cows, raising the specter of a “pink revolution” that he claimed had endangered cows and other cattle for meat export. After he was elected prime minister, Modi did not robustly condemn vigilante attacks by cow-protection groups until as late as August 2018, when he finally said, “I want to make it clear that mob lynching is a crime, no matter the motive.” In January 2019, he said these attacks did not “reflect well on a civilized society.” He, however, appeared to dismiss claims of growing Muslim insecurity as being politically motivated.

According to a survey by New Delhi Television, there was a nearly 500 percent increase in the use of communally divisive language in speeches by elected leaders—90 percent of them from the BJP—between 2014 and 2018, as compared to the five years before the BJP came to power. Cow protection formed an important theme in a number of these speeches.

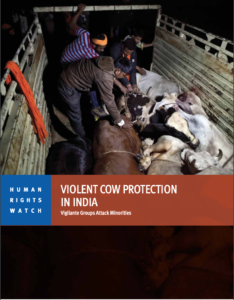

Cattle seized by cow vigilantes in a cow shelter in Barsana, Uttar Pradesh, June 2017.

© 2017 Cathal McNaughton/Reuters

In addition to beating up cattle traders and transporters that have caused serious injuries, even fatalities, cow protectors have reportedly assaulted Muslim men and women in trains and railway stations in Madhya Pradesh state, stripped and beat Dalit men in Gujarat, force-fed cow dung and urine to two men in Haryana, raided a Muslim hotel in Jaipur, and raped two women and killed two men in Haryana for allegedly eating beef at home.

In September 2015, a mob killed Mohammad Akhlaq, 50, in Uttar Pradesh state, and critically injured his 22-year-old son, over allegations that the family had slaughtered a calf for beef. Following public outrage—and because the state was then governed by an opposition party—the police made some arrests including of a local BJP leader’s son and relatives. The suspects’ Hindu supporters responded by damaging a police van and other vehicles. Several senior BJP leaders backed the alleged actions of the suspects. As a result, Akhlaq’s family had to leave the village in fear. More than three years later, the trial has yet to begin. All of the accused have been released on bail, raising fears among the victims’ families.

Hate Crime Watch, a collaborative database by the Indian organization FactChecker, documented 254 reported incidents of crimes targeting religious minorities between January 2009 and October 2018, in which at least 91 persons were killed and 579 were injured. About 90 percent of these attacks were reported after BJP came to power in May 2014, and 66 percent occurred in BJP-run states. Muslims were victims in 62 percent of the cases and Christians in 14 percent. These include communal clashes, attacks on inter-faith couples, and violence related to cow protection and religious conversions. Maja Daruwala, senior advisor to the civil society organization Commonwealth Human Rights Initiativesaid, “The obvious impunity for the string of crimes that have taken place, and their hugely shameful valorization by some leaders, is distinctly a strong factor in their continuation.”

| Examples of Remarks Made by Officials on Cow Protection

“We should not take law into our hands. But we have no regret over his death [Pehlu Khan] because those who are cow smugglers are cow-killers; sinners like them have met this fate earlier and will continue to do so.” |

Denying Accountability

Since 2014, several BJP-ruled states have passed stricter laws to prohibit the killing of cows and adopted cow protection policies that critics contend are populist gestures to promote Hindu nationalism. Many of the new legal provisions make cow slaughter a cognizable, non-bailable offense, putting the burden of proof on the accused, in violation of the right to be presumed innocent. Mrinal Satish, executive director of the Centre for Constitutional Law, Policy, and Governance at National Law University in Delhi, said:

In some of these laws where there is a shifting of burden and consequently a presumption of guilt, that should be very rarely used because it curtails fundamental liberties. The impact that it can have is that they can make certain professions such as that of transporters, butchers, leather workers, susceptible to the criminal process and the process itself ends up being the punishment in most cases.

Some state laws provide severe punishments for slaughtering cows, including life imprisonment. After Gujarat state amended its cow protection laws in 2017 to increase punishments, Pradeepsinh Jadeja, the minister for home affairs, said, “We have equaled the killing of a cow or cow progeny with the killing of a human being.”

Numerous policies introduced around cow protection by BJP-ruled state governments have enabled vigilante groups. Members of cow protection committees—sometimes alongside police—patrol streets and highways at night, stop vehicles, check them for cattle, intimidate drivers, and react with violence if they find cows. Said Sajjad Hassan, convener of Citizens Against Hate, a collective that documents hate crimes in India: “The police have effectively outsourced the identification and apprehension of the alleged violators of these cow protection laws.”

In 2016, the Haryana government set up a 24-hour helpline for citizens to report cow slaughter and smuggling, and appointed police task forces to respond to the complaints.

In March 2017, after becoming the BJP chief minister of Uttar Pradesh state, Adityanath, a Hindu cleric, ordered the closure of numerous slaughterhouses and meat shops, mostly run by Muslims.

In Rajasthan, the previous BJP state government opened six gau raksha (cow protection) police posts tasked with curbing cattle smuggling. These posts have become a hotbed for cow protection groups who target Muslim cattle traders, dairy farmers, and herders from Haryana, even if they have official purchase receipts for their cattle. In April 2017, a mob in Rajasthan brutally assaulted a 55-year-old dairy farmer, Pehlu Khan, and four others with sticks and belts and allegedly tore their purchase receipts. Khan died two days later from his injuries. Rajasthan’s home minister sought to defend the cow protectors by blaming the victims: “People know cow trafficking is illegal, but they do it. Gau bhakts [cow worshippers] try to stop them. There’s nothing wrong with that but it’s a crime to take the law in their [own] hands.”

The police themselves can feel threatened by these politically protected groups. Richhpal Singh, a former additional superintendent of police in Rajasthan, said the uptick in violence by cow vigilantes was political: “Police face political pressure to sympathize with cow protectors, and do a weak investigation and let them go free. These vigilantes get political shelter and help.”

Police Failure to Investigate and Prosecute

Instead of promptly investigating cow-protection attacks and prosecuting perpetrators, the police, in at least a third of the reported cases, have filed complaints against victims’ family members and associates under laws banning cow slaughter. Counter complaints against witnesses and family members have often served to make them afraid to pursue justice. In some cases, witnesses turned hostile because of intimidation both by the authorities and the accused.

In eight cases documented in this report, the police acted improperly: in two, they delayed filing First Information Reports (FIRs) required to begin an investigation into a crime; in two others, they violated procedures, even allegedly falsified details in one of them; and in four the police were allegedly complicit in the death of the victim and tried to cover-up the crime. The police were compelled to respond only after media criticism, protests, or intervention through the courts by human rights activists and lawyers.

In the killing of Imteyaz Khan and Mazlum Ansari in Jharkhand, the police arrested eight men, who all confessed to the killings and said they were members of a cow protection group that had previously threatened Muslim cattle traders. The police filed charges against all eight in May 2016, but did not include a prominent member of the local cow protection group, the only accused who had been named in the FIR filed by a witness to the case. In a glaring failure of procedure, none of the statements of the accused were recorded in front of a magistrate, even though a confession made to a police officer is not admissible as evidence under Indian law. The victims’ families told Human Rights Watch when the eight accused were released on bail in June 2016, they were scared for their safety. In December 2018, a court in Jharkhand convicted all eight accused and sentenced them to life in prison.

In some cases, alleged perpetrators enjoyed open political patronage. For instance, BJP minister Jayant Sinha welcomed the release on bail of the men convicted of killing Alimuddin Ansari in Jharkhand in June 2017, following their appeal of the conviction in a higher court. The released defendants had gone to thank Sinha for his legal assistance, where he garlanded them and posed for photographs. Wrote activist Harsh Mander: “It is this moral messaging that spurs lynch mobs in every corner of the country to turn upon their victims with the cruelty and loathing that has penetrated the souls of young people, even children.”

In December 2018, an angry mob set fire to a police station and burned several vehicles in Bulandshahr in Uttar Pradesh, after villagers found some animal carcasses they said were of slaughtered cows. Two people, including police officer Subodh Kumar Singh, were killed. The authorities transferred three police officials and arrested over 30 people. However, it was only after public criticism that the authorities arrested the two main accused, one a local leader of the Bajrang Dal, a militant youth organization ideologically affiliated to BJP, and the other a leader of the BJP youth wing. On the other hand, the police promptly arrested six men for cow slaughter and filed a case under the National Security Act (NSA)—a repressive law that permits detention without charge for up to a year—against three of them. Soon after the violence and killings, a senior police official said investigators were determined to prosecute those involved in slaughtering cows. “The cow-killers are our top priority. The murder and rioting case is on the backburner for now.”

In the case of Akbar Khan, who was killed in Alwar district in Rajasthan in July 2018, local BJP lawmaker Gyan Dev Ahuja demanded the release of the accused and the arrest of Khan’s associate, who had managed to flee the mob and was a witness to the case. Meanwhile, after an inquiry following media criticism, one police official was suspended and four others were transferred because they had allegedly deliberately delayed bringing Khan, who was critically injured, to the hospital. It took them three hours to reach the hospital, which was only 20 minutes away, because they reportedly stopped to drink tea and arrange transportation for Khan’s cows. Khan, alive when the police picked him up, was declared dead on arrival at the hospital.

The police response to the June 2018 mob attack on Samaydeen and Mohammad Qasim in Hapur district of Uttar Pradesh exposed complicity in covering up crimes. Qasim was killed and Samaydeen severely injured and hospitalized. However, the police allegedly filed a false report attributing the death to a motorbike accident. Samaydeen’s brother Yaseen told Human Rights Watch he put his signature on the FIR despite the false claim of a motorbike accident because of police threats:

The police would not tell us the hospital they had taken Qasim and Samaydeen. Then the police threatened us: “Unless you sign this FIR we will not tell you where Samaydeen is.” They also threatened us with arrest under cattle protection laws, saying they would put our whole family in jail. The police said, “Don’t you know whose government it is? What can happen? It’s better for you all to say nothing.”

In the case of Mustain Abbas, who was killed in Kurukshetra district in Haryana in March 2016, the High Court, hearing a habeas corpus petition by his father, determined the police had allowed cow protectors to “unleash terror” with impunity. In its final order, a month later after the police had finally filed a case of murder against four people, the court again found that the local administration appeared to be backing the vigilante groups and that “there is every likelihood that local police to save its officers and on account of political overtones is not likely to investigate this ugly incident in its entirety.” The court ordered the case be investigated by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). The CBI filed a fresh FIR in May 2016. However, at this writing more than two and a half years later, the investigation was still pending, and charges had yet to be filed.

Cow-Protection Vigilantes and Livelihoods

Vigilante attacks by cow protection groups and stricter laws on cow slaughter and transportation of cattle have disrupted India’s cattle trade and the rural agricultural economy, as well as leather and meat export industries that are linked to farming and dairy sectors.

India is the largest beef exporter in the world, exporting buffalo meat worth about US$4 billion a year. However, after the BJP government came to power in 2014, exports have mostly declined. The leather industry has also been affected, with a government economic survey noting that “despite having a large cattle population, India’s share of cattle leather exports is low and declining due to limited availability of cattle for slaughter.”

The government has authority to enact laws and policies restricting the buying and selling of cattle but, in doing so, need to guard against disproportionately harming minority communities and ensure that any such laws or policies are consistent with the right to a livelihood for all Indians.

Muslims and Dalits have been disproportionately affected by the laws, policies, and unlawful attacks harming cattle-related industries. Slaughterhouses and meat shops are mostly run by Muslims. Dalits traditionally carry out jobs to dispose of cattle carcasses and skin them for commercial purposes such as leather and leather goods. The resulting policies are harming entire communities, particularly farmers and laborers.

“It’s not just about Muslims,” said P. Sainath, an author, journalist, and expert on India’s agricultural economy. Previously, cattle owners, including many Hindus, who were unable to cope with the economic burden of keeping unproductive livestock, sold the cattle to slaughterhouses. Now, he said, forced to continue feeding and caring for them, many have simply abandoned the animals. This has caused problems for farmers with stray cattle destroying their crops.

M.L. Parihar, an author and agricultural expert, said: “The Hindutva leaders who are promoting this obsession with cows don’t realize how much loss they are causing to their own Hindu community, and damage they are causing to their country.”

Measures to Address Vigilante Violence

In July 2018, the Supreme Court in Tehseen S. Poonawalla & Ors. v. Union of India & Orsdirected central and state governments to publicly make statements and spread the message that “lynching and mob violence of any kind shall invite serious consequence under the law.” In response, the home minister told the parliament the government had formed a panel to suggest measures to stop mob violence in the country. “We will also bring a law if that is required,” he said.

The court also ordered all state governments to designate a senior police officer in every district to prevent incidents of mob violence and ensure that the police take prompt action against the perpetrators and safeguard victims and witnesses. It recommended a victim compensation scheme and said all such cases should be tried in fast-track courts, with victims or the family members given timely notice of any court proceedings including of applications for bail, discharge, release, or parole filed by the accused persons. Finally, the court said action should be taken against any police or government officials who fail to comply with these directives.

Thus far, several states have designated officers and issued circulars to police officials on addressing mob violence. However, most of the court’s other directives have yet to be complied with. Most states have not filed compliance reports and even those that have been filed do not provide details. Mohsin Alam Bhat, executive director of the Centre for Public Interest Law at Jindal Global Law School, said, “At best, these reports just indicate a formal implementation of the court’s guidelines.”

The failure of India’s central and state governments to protect minority communities from communal attacks by cow-protection vigilantes or take adequate steps to prosecute those responsible violates the rights to life, non-discrimination, equal protection of the law, and to pursue a livelihood. The government should not endorse or be complicit in using religious belief to advance discrimination against minority communities.

Key Recommendations

- Implement Supreme Court directives on preventing communal violence and ensuring that individuals responsible for mob attacks are held accountable;

- Ensure prompt and impartial investigation and prosecution of the perpetrators and instigators of communal attacks and investigate alleged police inaction in responding to vigilante violence; and

- Clearly and unequivocally signal, through public statements and measures by senior state and high-ranking police officials, that perpetrators in mob violence cases, even those politically connected, will be fully prosecuted.